The Federal Trade Commission’s (FTC) warning letters to eight companies that sell man-made diamonds and diamond simulants have clearly made an impact on that business.

One lab-grown seller told me that, after the news broke, he took a thorough look at all his communications. And even though his company was always extremely careful, it still changed a few things, out of prudence.

But that isn’t bad, he said. He found it a worthwhile exercise. Companies should hold themselves to high standards.

I checked another lab-grown e-tailer whose Facebook ads don’t seem to have much disclosure. Now—voilà—it’s been beefed up. Others still lag behind, which is perplexing, given that the FTC is clearly interested in this issue. Plus, if lab-grown diamonds are as popular as we keep hearing, why wouldn’t a seller tout their origin in its advertising?

None of this should have been a surprise. These issues—particularly regarding simulants—have been around for years. Some companies have been warned repeatedly about their lack of disclosure.

I’ve heard lab-grown sellers grumble that the FTC’s actions must have been spurred by pressure from big mining companies. There were similar conspiratorial murmurs from the natural industry after the FTC’s revisions last summer.

This is a misunderstanding of what the FTC’s role should be. It’s supposed to weigh the evidence, then decide. Clearly, its decisions—particularly on controversial issues—won’t always be popular. But, ideally, it shouldn’t be seen as favoring one side, or sector, over another. (I would also argue that there shouldn’t be “sides” here, and that’s part of the problem.)

You may not always agree with the FTC’s decisions or methods. I don’t. The actions and rulings of government agencies are fair game for criticism.

For instance, lab-grown seller Ada told me that it received an FTC warning letter for using the word cultured accompanied by #labdiamonds in three Instagram posts. That doesn’t seem likely to fail the “net impression” test. I’ve found Ada clear in its communications.

Of course, three posts didn’t take long to rectify. Other companies may have a bigger job ahead.

Take sellers of simulants—diamond look-alikes such as cubic zirconia. It’s certainly possible that terms such as diamond simulant gemstones, diamond hybrids, Nexus diamonds, or diamond alternatives could confuse consumers as to what they are buying, particularly if they are advertised with hashtags like #labgrown.

I’ve long argued that sellers shouldn’t be allowed to just call their product a simulant, but specify exactly what kind of simulant it is. The Jewelers Vigilance Committee (JVC) says that consumers who believe they are getting a diamond and end up with something that has little chemical relation to an actual gem are a growing part of its mediation practice. Ada cofounder Jason Payne, who runs a lab-grown buyback program, says that nearly 40 percent of the inquiries he gets are from people who mistakenly believed they were purchasing actual lab-grown diamonds, only to find out that they didn’t.

Yet, some will argue, these terms are scientifically accurate. But this also misses how the FTC sees its mandate.

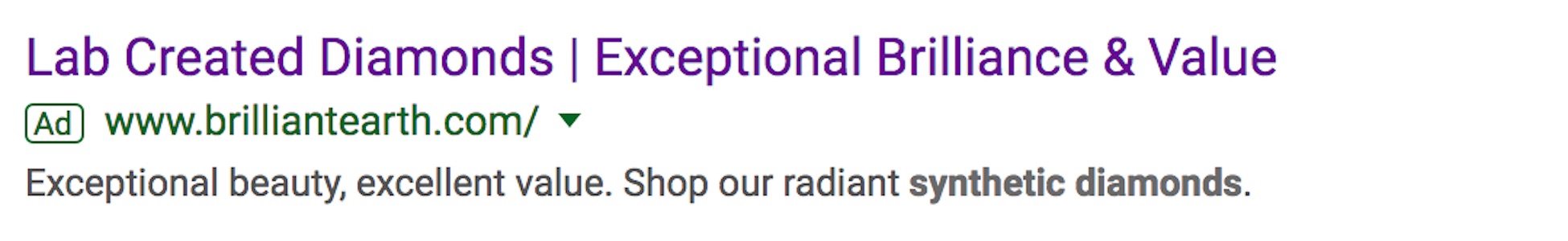

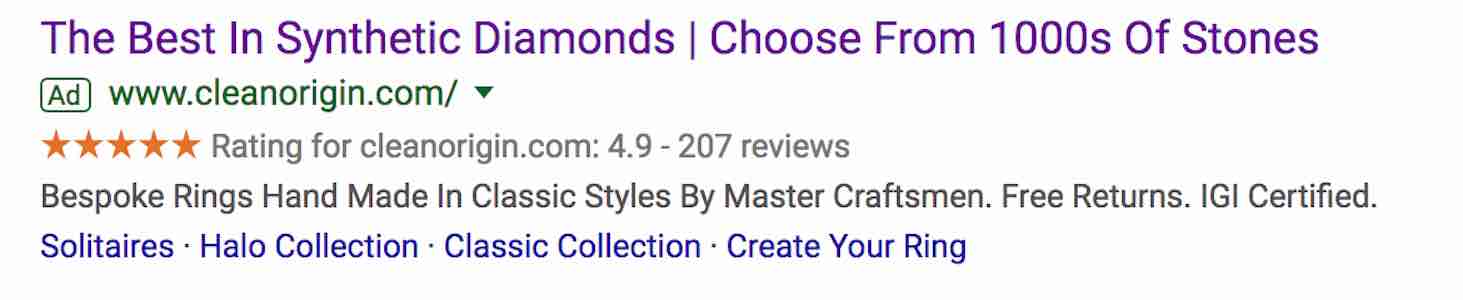

Take the word synthetic, which the FTC removed from its list of recommended descriptors. Some in the natural industry howled at this. Synthetic is scientifically accurate, they said. That’s true. But that’s not the standard here.

Phrases like above ground real diamonds may also be scientifically accurate, but they’re not on the list either, because the average consumer might not understand their meaning. Removing synthetic from the list is consistent with the FTC’s stated goals, since some consumers misunderstand it to mean “fake.”

Now contrary to some assertions, the FTC did not say that sellers could not use the term synthetic, though it did say that term couldn’t be used to imply a competitor’s lab-grown diamond is not an actual diamond. (It offered similar guidance for the terms natural and real. The Guides still caution against lab-grown companies using the terms natural, genuine, and real to describe their products.)

Synthetic is still used in scientific journals, and if you Google synthetic diamonds, you get these results:

Regardless, when synthetic is used in marketing, its meaning must be clear (i.e., something resulting from synthesis rather than occurring naturally).

That is also why the FTC discourages use of the terms eco-friendly or sustainable. It’s not about whether the claim has validity. The terms are nebulous; they mean both everything and nothing, as my friend Bill Furman used to say. Planting a tree is eco-friendly.

Growers argue that their process is eco-friendly in relation to mined diamonds. JVC president and CEO Tiffany Stevens addressed this best in National Jeweler:

One of the recurring issues we see with the environmental claims is the use of relative standards (i.e., Michelle speaks 20 words of Spanish and Tiffany speaks one, so Michelle is fluent in Spanish) rather than what the standard actually is under the [FTC’s] Green Guides, which is an absolute (i.e., Michelle is either fluent in Spanish or not, regardless of how competent the person standing next to her is).

Under this kind of comparative standard, a wide range of companies could dub themselves eco-friendly—simply because they have a lesser footprint than a competitor. If one company dumps 9,000 pounds of pollutants in the ocean, and another releases 8,500, the latter company shouldn’t be allowed to brag about its eco-friendliness—at least without notifying consumers it’s also a significant polluter.

Further, even the comparative claims are hard to justify, since we still don’t have independently verified (or really any) stats on the eco-footprint of lab-grown diamond products. Many lab-growns are made with large amounts of nonrenewable energy, which isn’t eco-friendly in any sense of the term, never mind the expansive meaning that the FTC believes consumers attach to it. (Anyone solely looking to help the environment should probably opt for recycled diamonds.)

If a product has beneficial environmental features, they need to be specific and spelled out. The assertion by Diamond Foundry—another FTC letter recipient—that it’s been “certified carbon neutral” by Natural Capital Partners seems to me a valid example of a specific, verifiable environmental claim (though I’d prefer more transparency about it). I can imagine others, though they need to be accurate. Check out the following in the Australian magazine Jeweller:

I recently attended a seminar where the presenter, whose family has been in the natural diamond business for generations, claimed that his own lab-created diamond brand was a new style of sustainable business, and eco-friendly.

He made all sorts of feel-good claims, which most of the audience gobbled up. I knew little about the presenter or his business, but a few others watching scoffed at some of his assertions.

One told me that this particular synthetic diamond business had previously claimed its factory used wind-power— sustainable energy—however, a Google satellite image of its location showed no evidence of wind-power generation plants!

Environmental marketing is a potentially powerful force that might do real good for the planet. But, that won’t happen if it becomes more about the “marketing” than the “environment.”

The larger point is, if a business chooses to ignore the FTC Guides, or to interpret them in fanciful ways, it does so at its own risk. And that goes for any part of the diamond or jewelry industry.

The FTC has proven itself unpredictable lately, but in a way that’s a good thing. It shouldn’t be on anyone’s side but consumers’.

UPDATE: This story has been updated to clarify that the FTC Guides caution against lab-grown companies using the term genuine, natural, and real.

(Image courtesy of the Diamond Pro)

Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazineFollow JCK on Twitter: @jckmagazine

Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine