Our chronicle of silver jewelry spans several centuries and includes intriguing historical facts, exemplary works from iconic makers, and insights from the modern-day designers who are elevating the white metal to an art form

“You just can’t beat the elegant gleam of silver against gray cashmere or buttery soft suede,” declared fashion editor Patricia Peterson in a 1974 edition of The New York Times. Highlighting silver jewelry from Elsa Peretti, Barry Kieselstein-Cord, and Georg Jensen, and a bracelet “handmade to perfection by M&J Savitt,” this tiny two-page trend report is one of many primary sources that attest to the metal’s popularity in the 1970s.

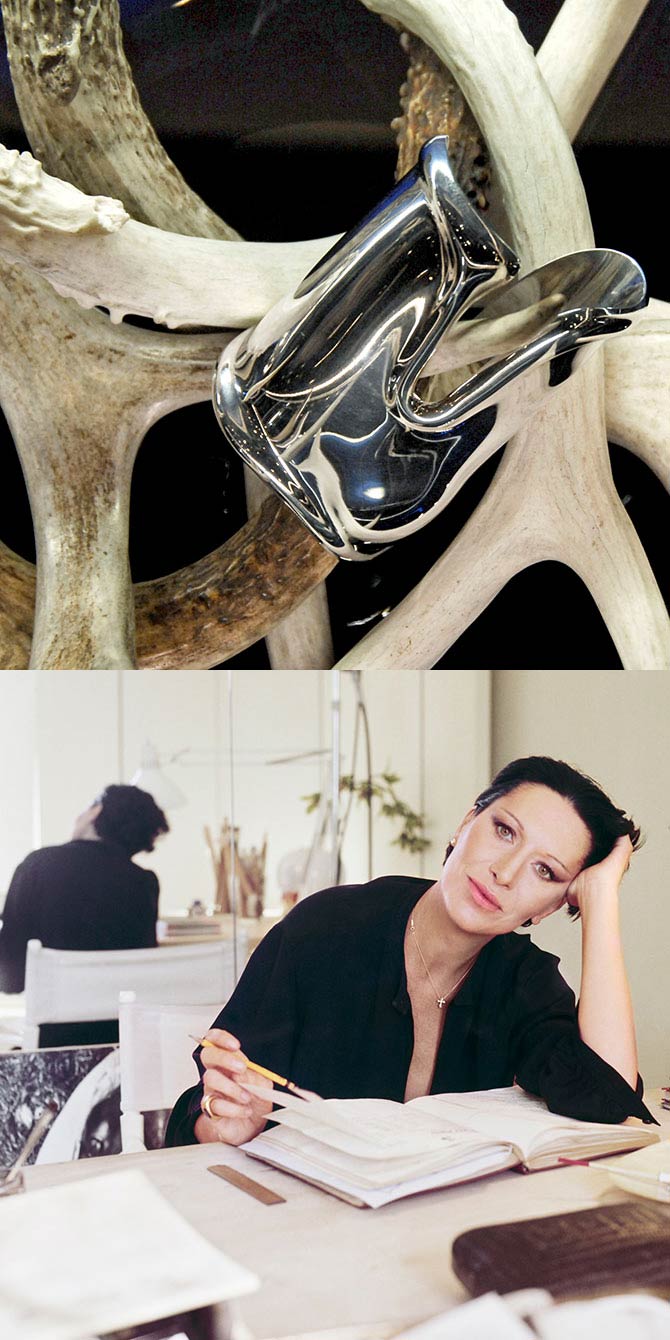

By 1975, Peretti’s creations had arrived at Tiffany & Co., marking the first time silver appeared in the store’s jewelry department. The retailer’s embrace of the metal conveyed an essential fact to the era’s most sophisticated consumers: that silver’s “elegant gleam” was not merely the height of fashion, but something to be cherished and worn as a status symbol.

As any art historian will tell you, however, silver first seduced humankind long before the Me Decade.

“It has been prized by nearly all cultures with access to the metal since antiquity,” says Jeannine Falino, curator of “New York Silver: Then and Now,” an ongoing exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York. According to Falino and her colleagues, silversmiths who were in the business of crafting and retailing decorative items for the home were among the early European settlers in America. “The creation and use of silver adornments was an extension of age-old European traditions,” she says, adding that some of the silver objects made during the 18th and early 19th centuries included shoe buckles, brooches set with garnets or paste, and academic medals.

Silver Pioneers

Between 1500 and 1800, Spain was the world leader in silver production; in fact, more than 85 percent of the world’s silver came from Spanish-owned mines in the New World, particularly in Bolivia, Peru, and Mexico. There were no known deposits of silver ore in North America; even so, Native Americans in the Southwest came to produce silver jewelry as a result of their dealings with the Spanish.

“By the mid-19th century, nearly all the silver used in America came from coins or melted objects,” Falino says. New discoveries in the Sierra Nevadas would change all that. Following the 1859 rush of prospectors responding to the Comstock Lode, the largest and most famous American strike, the United States retained the title of the world’s largest silver producer until about 1900. And as a result, silver jewelry and fine silver flatware and decorative objects for the home became available to a growing middle class.

From the early to mid-20th century, silver jewelry made in Mexico, and across the pond in Scandinavia, was having a heyday, and vintage pieces from these places are very much in demand today.

In Mexico, Taxco is the most recognized mark, denoting the area in which hundreds of artisans have worked, and continue to work. Many of the most prized Taxco pieces originated from the workshop of the American silversmith William Spratling.

“Spratling combined traditional Mesoamerican motifs with European design for a look that is now classically considered midcentury Mexican,” says Ariana Boussard-Reifel, whose vintage jewelry business, Marteau, is heavily focused on silver jewelry. In-the-know dealers and collectors tend to favor work by Taxco artists such as Margot de Taxco (born Margot Van Voorhies), Antonio Piñeda, and the families that founded Los Castillo and Los Ballesteros.

The majority of jewelers are perhaps more familiar with the Danish master metalsmith Georg Jensen, who founded his Copenhagen workshop in 1904. Jensen’s distinctive style is as highly regarded, and as enduringly influential, as Peretti’s, and though one debuted 70 years earlier than the other, both have been able to sustain widespread appeal among multiple generations of customers. The house of Georg Jensen is still in operation today, and the newly minted jewelry and objets have the same sculptural, elegantly minimalist quality that made the early pieces such a hit with sophisticated American consumers in the post–World War I era.

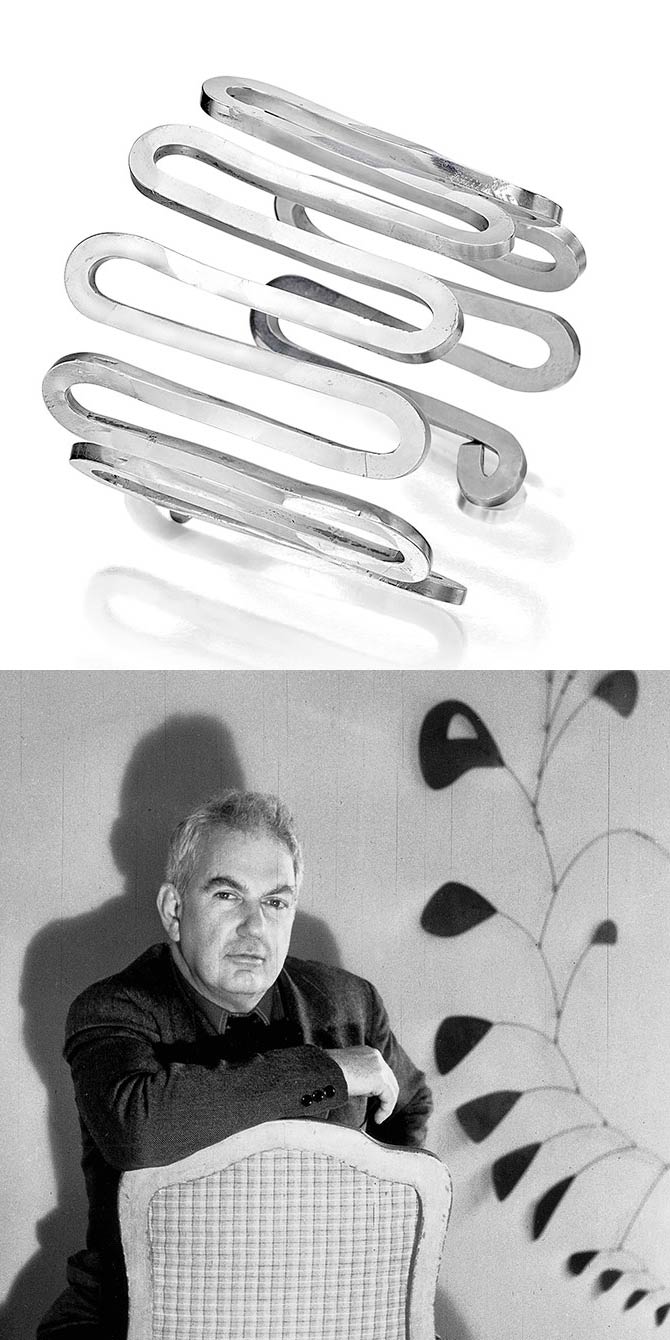

American artist Alexander Calder, best known for his mobiles, is also revered for his silver jewelry. He flourished in this medium in the 1930s and 1940s. Lee Siegelson, a New York City–based antique dealer of rare, museum-quality jewels, places Calder alongside the famous French jewelry designers Jean Després and Jean Dunand. “They’re really the pinnacle of rare, exceptional silver jewelry, along with a few Cartier things,” he says.

Silver Revivalists

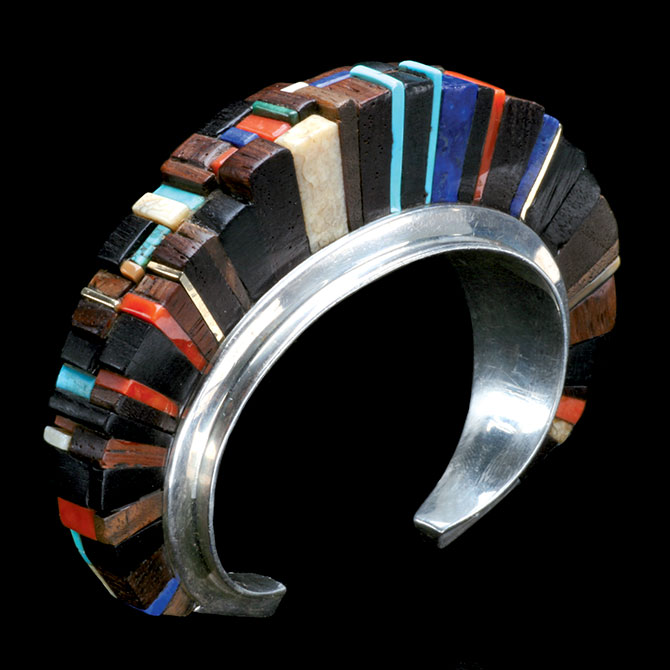

And if vintage Calder isn’t in the budget? “There’s currently a flourishing body of Native American jewelers in the Southwest, most of whom use silver as the foundation of their work,” Falino says. “All of them are indebted to Charles Loloma, who led the way in the early 1960s with silver bracelets set with turquoise, ivory, and coral.” (Loloma, a Hopi jeweler from Arizona, is considered the father of contemporary American Indian jewelry.)

Before David Yurman and John Hardy became household names in the 1990s, New York City–based designer Robert Lee Morris spiked a silver jewelry revival in the 1980s. After collaborating with fashion designer Donna Karan on a few runway shows, Morris told the Chicago Tribune in 1986 that he was going for an “icy, frosted” look to complement Karan’s spring line.

“Gold is a really powerful punctuation on a dark surface,” he said. “Matte silver has a softening effect, a lighter feel.” Morris had been trying for years to develop a soft satin finish for silver and finally found that brushing silver’s surface with “millions and millions of tiny, tiny scratches” was the thing.

Morris-signed pieces had cachet, but wholesale jewelry manufacturers saw an opportunity to mass-produce affordably priced silver hoops, cuffs, and “neck rings” with on-trend matte and hammered surfaces. Not to mention huggies, herringbone chains, and pendants set with semiprecious stones—remember those?

The financial crisis of 2008 only burnished silver’s appeal, as designers accustomed to working in gold embraced the more affordable metal. (At press time, the price of silver was $16.73 per ounce. Even though it hit $48.70 in April 2011, the price still, yes, paled in comparison with its sister precious metal.)

Today, there are a number of silver mines operating in Mexico; in Peru, Bolivia, and other South American countries; and in the United States and Australia. But with the exception of some of the larger jewelry houses, over the past five years it’s become industry standard to use refined silver, which is melted from old jewelry, silverware, and industrial goods.

Silver Devotees

Regardless of its origins, fine silver jewelry is still a status symbol. David Yurman’s distinctive yet ubiquitous cable bracelet and John Hardy’s Balinese-inspired cuffs and Jaisalmer dotted hoops continue to be favored by women of taste and means, especially those who appreciate wearing brands with easily identifiable hallmarks.

Silver’s affordability, however, means today’s smartest retailers are encouraging their smaller brands to develop bridge collections done in silver, and to introduce two-tone metal styles as a way to make their pieces more accessible to a wider, often younger audience.

They’re also investing in talented artisan designers—those who shape, chase, and tumble the metal by hand and create custom finishes and patinas. Mexican jeweler Daniel Espinosa emerged from such artisanal ranks and now oversees a thriving factory in Taxco, producing fashion-forward silver jewels for a global audience. Meanwhile, his U.S. counterparts continue to find new things to love about the metal.

“Silver is a wonderful material to experiment with,” says New York City–based designer Elizabeth Garvin. “It’s lightweight and very malleable. It also enables me to make larger, sculptural pieces with considerable strength, integrity, and longevity.”

Martha Seely, a designer based in the Boston area, is equally keen on the metal. “Because silver is such a soft metal, it moves with every stroke of a hammer and accepts texture, shape, and form so easily,” she says. “Sometimes it feels more like clay than a hard metal.”

And modern silver jewelry doesn’t have to be a super-shiny “bright white.” Boussard-Reifel, who designs an eponymous line of contemporary jewelry, likes her silver pieces to have a “moon-like glow,” while Garvin feels that silver “just wants to be dark.”

When Garvin first conceived her fine jewelry collection using silver, there was no question that it would be oxidized. “A piece of fine jewelry should not have a temporary quality to it, nor a look that’s not meant to last,” she says. “Oxidation is actually a natural process, very slow when left alone, but with chemistry the process can be sped up and controlled for consistent results.”

Garvin’s devotees and her many supportive retailers love her signature look of white diamond baguettes set in oxidized silver. “It’s the contrast, and maybe the contradiction as well—formally understated, but visually dazzling,” she says. “But there are very real limits to the strength of silver, even when alloyed, so as a jeweler you need to know those limits to set precious gems securely.”

Silver also allows for the creation of bold, oversize pieces—think Wonder Woman–worthy statement cuffs, dramatic pendants decorated with hand-cut and overlaid patterns, and repoussé brooches—for less money.

“Compared to the cost of gold or platinum, silver is financially accessible to most people,” Seely explains. “I believe every woman should be able to afford to buy some of the beautiful jewelry she loves. And it should not have to be base metal simply plated with a whisper of fine metal on the top.”

Top: 1860s: silver miners rushing Nevada’s Comstock Lode; 1880s: a Navajo silversmith; 1900s: Danish silversmith Georg Jensen founded his workshop in Copenhagen in 1904, but his influence spanned decades, as seen in this 1947 necklace by protégé Henning Koppel.

(Comstock Lode: Everett Collection; Navajo silversmith: Ben Wittick Collection/Palace of the Governors Photo Archives/New Mexico History Museum, Santa Fe; Koppel necklace: Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum/Art Resource, N.Y.; Calder bracelet: courtesy of Siegelson; Calder: © Agip/Rda/Everett Collection; Spratling necklace: Museum Associates/LACMA, courtesy of the Ulrich Family, Licensed by Art Resource, N.Y.; Loloma bracelet: Robert K. Liu Photography for Ornament Magazine; Elsa Peretti bracelet: Nick Hunt/Patrick McMullan/Getty Images; Peretti: Horst P. Horst/Condé Nast/Getty Images; Robert Lee Morris necklace: courtesy Skinner Auctioneers/skinnerinc.com)