The jeweler’s role has certainly changed over the past 150 years, not just in fine-tuning a store’s merchandise mix, but in defining—and redefining—how merchandise is classified and understood by consumers. Here, we examine the oft-changing—and ever-confusing—lexicon for costume/fashion, bridge, demi-fine, and fine jewelry, and highlight the ways JCK has helped jewelers navigate the shifting boundaries between categories throughout the decades.

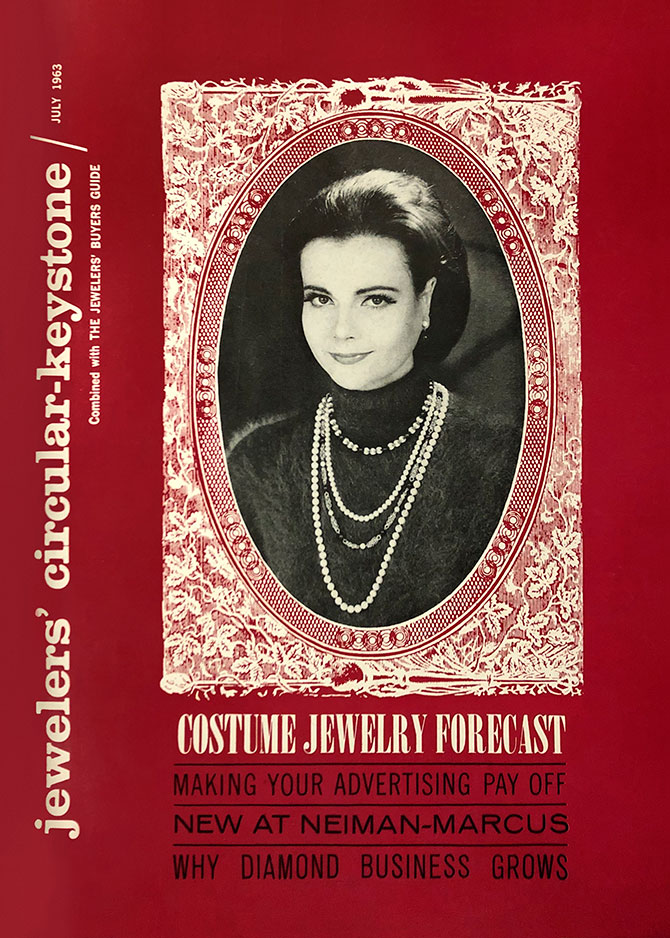

Costume/Fashion Jewelry

Defined as jewelry made from materials such as base metal, glass, and synthetic gems, costume jewelry was born out of demand for fine jewelry by those who couldn’t afford the real thing (see Guy de Maupassant’s classic 1884 story, “The Necklace,” for a perfect example of how women with more style than means adorned themselves—by embracing paste, an artful but worthless glass used in imitation jewelry).

In the 1920s, however, designer/ style icon Coco Chanel flipped the script by making layers of faux pearls and costume jewelry chic. Soon, even women obsessed with precious stones were proudly flaunting their fakes. JCK seized on the vogue in a 1930 article titled “Sell Costume Jewelry to Express Women’s Own Individuality.”

Today, fashion jewelry is preferred over costume jewelry to emphasize trends. Apparel designers from Badgley Mischka to Givenchy license their names for affordable fashion jewels that serve as brand entry points (a Marchesa wedding gown can run $10,000; Marchesa earrings cost as little as $35).

In doing so, they’ve complicated an already-polarized market, in which fast-fashion chains like Zara and H&M churn out cheap private-label pieces, while designer-fashion heavyweights—such as the perennially in-demand Alexis Bittar—create a niche for pricey, heirloom-style fashion jewels by cultivating celebrity and social media followers.

Bridge Jewelry

Despite silver’s millennia-rich roots in various cultures, sterling silver wasn’t celebrated in the United States as bodily adornment until the second half of the 20th century. Prior to then, jewelers associated it with home items and giftware. In 1895, The Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review devoted an article to spoon patterns and their provenance, emphasizing the importance of the “silver spoon” to the elite customer.

But as formal dinners waned, jewelers began to treat silver as wearable. As we wrote in 1975: “Say ‘sterling’ to a jeweler and he’ll reply ‘flatware’ or—these days—maybe he’ll say ‘jewelry.’ After reading this story, he may want to add ‘design’ to his list of responses.”

The term bridge jewelry ultimately joined the lexicon—to denote a bridge between costume and fine, most of it rendered in silver—although when that happened is murky. Experts concur that the term was coined by department stores, which often had bridge jewelry buyers yet sold that jewelry under the sterling silver label or even as designer pieces, depending on brand and styling. Regardless of what it referred to, bridge was always a trade term. “I’m fairly certain that consumers do not refer to, or think of, departments as bridge,” says Michael Barlerin, president of the Silver Promotion Service.

Bridge departments are also fluid. “In the late 1980s, I was an assistant buyer for bridge jewelry at Macy’s,” says Karen Giberson, president of the Accessories Council. “When the costs of sterling and gold soared, much sterling was moved to fine departments and many designers who only worked in gold expanded into silver.”

David Yurman, of course, took silver to a whole new level. “When we started our business, gold was in the front of the store and silver was in the back,” he says. “We helped change all of that, bridging fine and fashion jewelry.”

Today, some bridge jewelry is unbranded, but designer bridge is increasing. “Buyers see our brand in the bridge jewelry price point, but we truly believe we are in a white space in the market, offering intricately designed sterling silver jewelry at an accessible price point,” says Brooklyn, N.Y.–based Freida Rothman, who sells to jewelers, fashion boutiques, and department stores.

Demi-Fine Jewelry

The relatively new term demi-fine falls between bridge and unequivocally fine. Think lightweight pieces in karat gold and diamonds with hip styling at affordable prices. Aimed at 20- and 30-somethings seeking individuality and customization, the necklaces, rings, earrings, and bracelets can be mixed, matched, stacked, and worn in multiples. Brands like Brooklyn’s Wwake and Los Angeles’ Adina Reyter sell their demi-fine designs to fashion boutiques as well as jewelry stores.

“We call this delicate jewelry fashion fine or demi-fine, and the idea is that the wearer becomes the designer by how she mixes and matches it,” says Wwake designer-owner Wing Yau.

E-tailer Net-a-Porter expanded its jewelry business into the demi-fine category in late 2016, describing it as “serious jewelry that doesn’t take itself so seriously.” Since then, the number of demi-fine brands on the site has grown by 250%, according to reports.

Ground zero for demi-fine jewelry may well be the Brooklyn boutique Catbird, where customers can get a 14k Forever Sweet Nothing bracelet welded on to their wrist for a mere $94.

Fine Jewelry

And what about fine jewelry, classically defined as 14k or 18k gold or platinum set with precious gems?

Even that seemingly incontrovertible term has caused debate. In 1984, JCK editor-in-chief George Holmes wrote a story validating gold-filled as fine jewelry (gold-filled features 5% gold by weight defined by karatage; gold-plated refers to a thin layer of gold over brass that quickly wears off). Titled “Inexpensive Needn’t Mean Cheap,” his editorial suggested a slogan: “14 karat gold-filled: beauty and quality you can afford.” But his campaign failed to take root.

The more pertinent question may be: Do labels matter in a world defined by boundary-breaking artists like Yurman? If you ask us, not at all. Whereas jewelry was once categorized on the basis of one simple test—real or fake—decades of cross-pollination have resulted in a fashionable fusion of styles, materials, and price points that give today’s consumers the one thing they truly deserve: choice.

Top: Colored paste and enamel Strutting Peacock brooch in sterling silver, circa 1900; $875; info@vintageluxury.com

(Chanel: Roger Viollet/getty; Trifari: Jay B. Siegel/chicantiques.com; peacock: vintageluxury.com)