The diamond industry is so multifaceted that we could fill a whole issue with developments and innovations. For now, we’ll limit ourselves to the 5 biggest throughout JCK’s history.

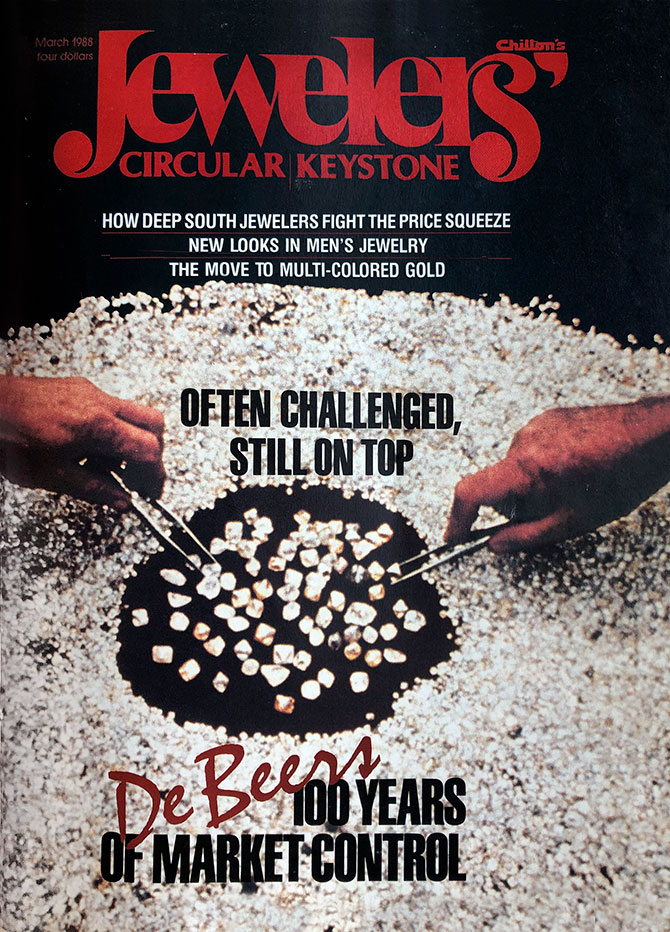

1888: De Beers Is Formed

In 1888, one year after JCK predecessor The Keystone Weekly was founded, there was an even more notable introduction: De Beers Consolidated Mines Ltd. founder Cecil Rhodes had spent years in the South African diamond fields gathering all the mines under a single umbrella. He believed that if De Beers maintained tight control over diamond production, the price would never go down, and diamonds would always be considered valuable.

“We can produce three, even four times present quantities,” The Jewelers’ Circular and Horological Review quoted Rhodes as saying in 1894, “but what we shall produce is just what the market requires.” Eight years later, the notorious racist and imperialist was dead at age 48. But his cartel model governed the diamond business for more than a century, until a combination of antitrust regulators and new competitors forced De Beers to give up the Rhodes map.

Top: Knysna Chameleon medallion with colored rough and polished diamonds, recut baguettes, and 1.3 ct. radiant-cut diamond; price on request; debeers.com

1938: De Beers Starts Advertising

1938: De Beers Starts Advertising

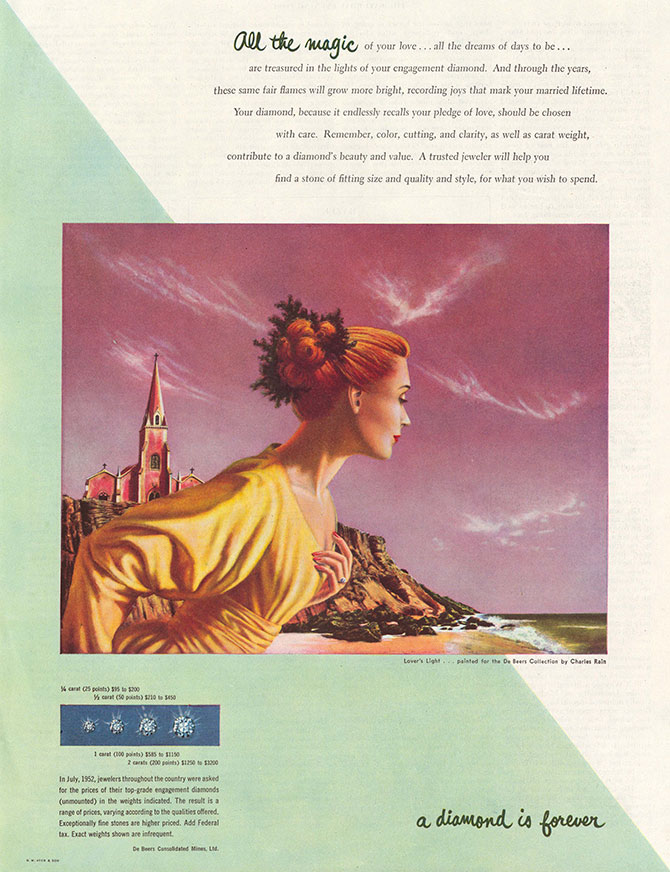

At first, advertising diamonds was considered a radical idea that would diminish the product. But faced with dwindling sales during the Great Depression, in 1938 De Beers director Harry Oppenheimer, the son of De Beers’ chairman Ernest Oppenheimer, enlisted New York City agency N.W. Ayer & Son to work a little marketing magic. Thus began a nearly six-decade partnership, whose ad and public relations campaigns were so successful the trade is still wondering how to duplicate them.

In 1947, copywriter Mary Frances Gerety penned its signature line, “A Diamond Is Forever.” In 2000, Advertising Age named those four potent words “the slogan of the century.”

A historic “A Diamond Is Forever” ad (Forevermark brought back the line in 2015)

1950s–1970s: The Industry Gets “Commoditized”

1950s–1970s: The Industry Gets “Commoditized”

After World War II, the diamond market’s nomenclature was a mess, with companies describing stones with vague, often misleading terms like AAA and top white. GIA executive director Richard T. Liddicoat yearned to bring order to the chaos. In 1953, he developed the GIA grading system for color and clarity, starting the color scale at D to avoid misuse. The first GIA diamond reports appeared two years later. Together, the grading scale and lab created “the first universal diamond language,” wrote Jewelers’ Circular-Keystone editor emeritus Donald McNeil in 1981.

Three years earlier, the premiere of the Rapaport Diamond Report had expanded that language further. Following a bit of tumult, the trade adopted “the list” as its price benchmark, though the mixed feelings never really went away. A December 1987 JCK article quoted this 47th Street maxim: “I have De Beers telling me how much to pay for my diamonds. I have the GIA telling me how good they are; I have Rapaport telling me how much I can [charge]…. What’s left?”

The Arcot II, a 17.21 ct. internally flawless D color diamond (sold at Christie’s in June for $3,375,000)

1980s: The Rise of India

1980s: The Rise of India

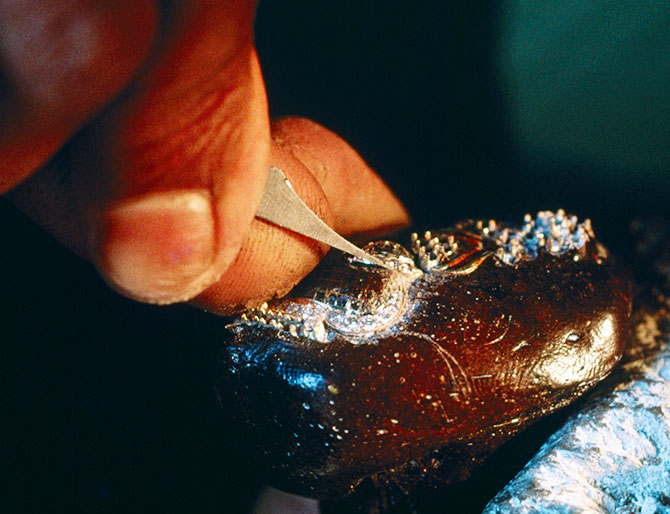

India is where diamonds were discovered, but for most of the 20th century, it didn’t play a big role in the diamond business. In 1983, Australia’s Argyle mine began producing large amounts of what were then considered “near gems.” Mass-market retail began to boom in the United States, creating a huge demand for price-point jewelry. Yet the labor required to cut the small Argyle stones often cost more than they were worth. Only India, with its large low-wage labor pool, could make it work.

As the trade there grew larger, so did the diamonds. The Indian industry “has the ability to take everything,” an Argyle exec told JCK in 1996. Today, 90% of diamonds are manufactured in India, turning once-thriving cutting hubs in Israel, Belgium, and New York City into virtual ghost towns.

A diamond cutter at work in Bombay in 1989

2000s: The End of the Cartel & the Beginning of the Kimberley Process

2000s: The End of the Cartel & the Beginning of the Kimberley Process

The summer of 2000 marked the unofficial end of the old diamond era and the beginning of the current one. On July 12 of that year, De Beers debuted its Supplier of Choice initiative and began to turn the page on over a century of market monopoly. Within a decade, it had sold off its $5 billion stockpile and watched its share of the market—which traditionally hovered around 80%—shrink to the low 30s. In 2012, the miner settled its antitrust issues in the United States, after decades of executives not being allowed to set foot here.

Right after the De Beers announcement came a fateful World Diamond Congress, where the industry, under fire over the conflict diamond trade, agreed to the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme. “Participants were hopeful that the industry had made genuine progress in putting this damaging and morally troubling issue behind it,” JCK wrote.

It didn’t quite work out that way. But after that summer, it was clear: The diamond industry could no longer do things its own way. It was now part of the wider world.

An artisanal miner pans for diamonds in Koidu, Sierra Leone, in 2012

(Diamond cutter: Sophie Elbaz/Sygma/Getty; Sierra Leone: Finbarr O’Reilly/Reuters/Newscom)