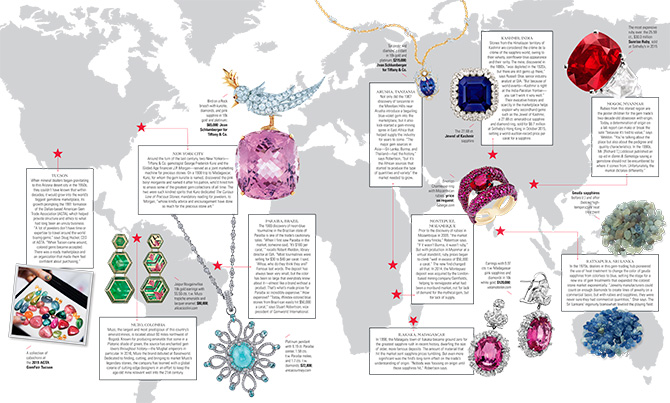

Over the course of JCK’s century and a half–long history, the gem trade has blossomed into a $10 billion business. We chronicle the most important developments in a world gone mad for hue.

Tucson

Tucson

When mineral dealers began gravitating to this Arizona desert city in the 1950s, they couldn’t have known that within decades, it would grow into the world’s biggest gemstone marketplace, its growth prompting the 1981 formation of the Dallas-based American Gem Trade Association (AGTA), which helped provide structure and ethics to what had long been an unruly business. “A lot of jewelers don’t have time or expertise to travel around the world buying gems,” says Doug Hucker, CEO of AGTA. “When Tucson came around, colored gems became accepted. There was a ready marketplace and an organization that made them feel confident about purchasing.”

Above: A collection of cabochons at the 2019 AGTA GemFair Tucson

New York City

Around the turn of the last century, two New Yorkers—Tiffany & Co. gemologist George Frederick Kunz and the Gilded Age financier J.P. Morgan—served as a joint marketing machine for precious stones. On a 1908 trip to Madagascar, Kunz, for whom the gem kunzite is named, discovered the pink beryl morganite and named it after his patron, who’d hired him to amass some of the greatest gem collections of all time. The two were such kindred spirits that Kunz dedicated The Curious Lore of Precious Stones, mandatory reading for jewelers, to Morgan, “whose kindly advice and encouragement have done so much for the precious stone art.”

Paraiba, Brazil

The 1989 discovery of neon-blue tourmaline in the Brazilian state of Paraiba is one of the trade’s cautionary tales. “When I first saw Paraiba in the market, someone said, ‘It’s $180 per carat,’ ” recalls Robert Weldon, library director at GIA. “Most tourmalines were selling for $30 to $40 per carat. I said, ‘Whoa, who do they think they are?’ Famous last words. The deposit has always been very small, but the color has been so large that everybody knew about it—almost like a brand without a product. That’s what’s made prices for Paraiba so incredibly expensive.” How expensive? “Today, Windex-colored blue stones from Brazil can easily hit $50,000 a carat,” says Stuart Robertson, vice president of Gemworld International.

Muzo, Colombia

55.56 cts. t.w. Muzo trapiche emeralds and

lacquer enamel; $80,000; alicecicolini.com

Muzo, the largest and most prestigious of this country’s emerald mines, is located about 60 miles northwest of Bogotá. Known for producing emeralds that come in a Platonic shade of green, the source has enchanted gem lovers throughout history—the Mughal emperors in particular. In 2016, Muzo the brand debuted at Baselworld. Dedicated to finding, cutting, and bringing to market Muzo’s legendary stones, the company has teamed with a global coterie of cutting-edge designers in an effort to keep the age-old mine relevant well into the 21st century.

Arusha, Tanzania

Arusha, Tanzania

Not only did the 1967 discovery of tanzanite in the Merelani Hills near Arusha introduce a beguiling blue-violet gem into the marketplace, but it also kick-started a gem-mining spree in East Africa that helped supply the industry for years to come. “The major gem sources in Asia—Sri Lanka, Burma, and Thailand—had the history,” says Robertson, “but it’s the African sources that started to produce the type of quantities and variety” the market needed to grow.

Tanzanite and diamond pendant in 18k gold and platinum; $215,000; Jean Schlumberger for Tiffany & Co.

Kashmir, India

Stones from the Himalayan territory of Kashmir are considered the crème de la crème of the sapphire world, owing to their velvety, cornflower-blue appearance and their rarity. The mine, discovered in the 1880s, “was depleted in the 1920s, but there are still gems up there,” says Russell Shor, senior industry analyst at GIA. “But because of world events—Kashmir is right at the India-Pakistan frontier—you can’t work it very well.” Their evocative history and scarcity in the marketplace helps explain why secondhand gems such as the Jewel of Kashmir, a 27.68 ct. emerald-cut sapphire and diamond ring, sold for $6.7 million at Sotheby’s Hong Kong in October 2015, setting a world-auction-record price per carat for a sapphire.

Mogok, Myanmar

Rubies from this storied region are the poster children for the gem trade’s two-decade-old obsession with origin. Today, a determination of origin on a lab report can make or break the sale “because it’s tied to value,” says Weldon. “You’re talking about the place but also about the pedigree and quality characteristics. In the 1990s, Mr. [Richard T.] Liddicoat published an op-ed in Gems & Gemology saying a gemstone should not be encumbered by where it comes from. Unfortunately, the market dictates differently.”

Montepuez, Mozambique

Prior to the discovery of rubies in Mozambique in 2009, “the market was very finicky,” Robertson says. “If it wasn’t Burma, it wasn’t ruby.” But with production in Myanmar at a virtual standstill, ruby prices began to climb “well in excess of $50,000 a carat.” The new find changed all that. In 2014, the Montepuez deposit was acquired by the London-based mining company Gemfields, helping to reinvigorate what had been a moribund market, not for lack of demand for the mythical gem, but for lack of supply.

Ratnapura, Sri Lanka

Ratnapura, Sri Lanka

In the 1970s, dealers in this gem-trading hub pioneered the use of heat treatment to change the color of geuda sapphires from colorless to blue, setting the stage for a new era of gem treatments that expanded the colored stone market exponentially. “Jewelry manufacturers could count on enough diamonds to create lines of jewelry on a commercial basis, but with rubies and sapphires, they were never sure they had commercial quantities,” Shor says. The Sri Lankans’ ingenuity (somewhat) leveled the playing field.

Geuda sapphires before (l.) and after (r.) high-temperature heat treatment

Ilakaka, Madagascar

In 1998, the Malagasy town of Ilakaka became ground zero for the greatest sapphire rush in recent history, dwarfing the size of older, more famous deposits. The amount of material that hit the market sent sapphire prices tumbling. But even more significant was the find’s long-term effect on the trade’s understanding of origin. “Nobody was focusing on origin until those sapphires hit,” Robertson says.

(Cover: Jean-Philippe Malaval; AGTA GemFair: courtesy of Danielle Miele/gemgossip.com; kunzite: Carlton Davis; tanzanite: © Tiffany & Co.; Jewel of Kashmir: courtesy of Sotheby’s; geuda sapphires: specimens by John Emmett, photos by Wimon Manorotkul/Lotus Gemology, Bangkok)