For just about any jewelry designer, landing a designer residency—or having any on-the-floor presence—at Bergdorf Goodman is the pinnacle of career success. Just ask London-based, German-born designer Sabine Roemer, who is celebrating her 30th year in the jewelry industry, an accomplishment that happened to dovetail with a star turn at Bergdorf’s this past winter.

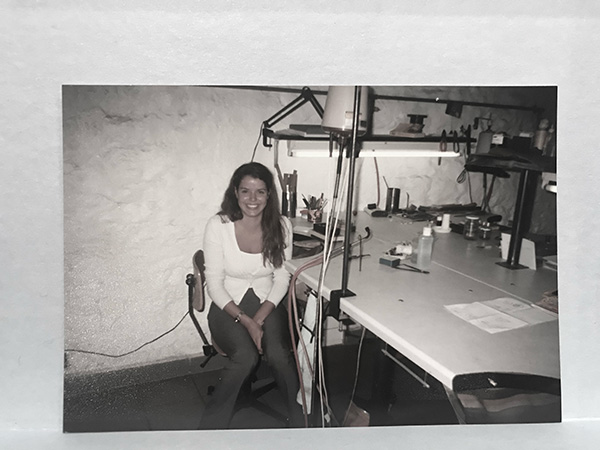

But long before this glorious moment, Roemer was just a girl at her bench. The year was 1995. And at only 15 years old, she was working with a master jeweler in Karlsruhe, Germany, a town near Pforzheim, the country’s famous gold and watch center.

The jeweler, says Roemer, “brought me to the workshop, showed me all the tools, and he said, ‘Listen, after these five days, you probably can have one piece done, and then you can take it home.’ And I made six pieces in five days. He was as astonished as me.”

It was at that point Roemer decided jewelry design and benchwork would be her vocation. To receive formal training, Roemer attended the prestigious Pforzheim Goldsmith and Watchmaking School; by the time she was 23, she was among the youngest female students to graduate from the program with a master’s degree.

In 2004, she moved to London and landed her job, a position with the celebrated jeweler Stephen Webster; she went on to produce work for Graff as well as a number of small ateliers up and down Bond Street. Ultimately she found her niche in high jewelry—with a feminine whimsical touch—and cultivated a network of devoted private clients.

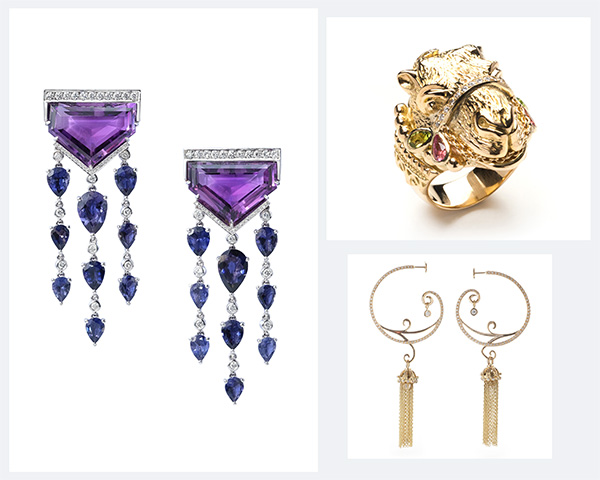

Over the next two decades or so, Roemer would sell at some of the world’s most prestigious retailers, exhibit pieces at the Cannes Film Festival, and receive several awards. She also created gem-set sculptures for Nelson Mandela and his foundation, and designed bespoke pieces for Angelina Jolie (a gold corset) and Morgan Freeman (bracelets).

Ahead, a Q&A with Roemer as she looks back on these and other career plot points—and reveals what she has discovered about herself along the way. (Interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.)

Over the past 30 years, what have been the biggest changes in the industry?

Nowadays, when it comes to jewelry design, you can see how a computer has spit out the piece instead of it being touched by human hands. One positive change I see is a return to going to your old-school jeweler on the corner to get something special that can’t be duplicated. Jewelry is so personal—you wear it. it touches your skin, it becomes part of you. Your energy is there and remains when you pass the piece down. I think the romantic and meaningful aspects of jewelry are coming back.

Obviously, another big change is women—the fact that they don’t need to be gifted jewelry anymore. They make their own money, they can go and buy jewelry for themselves.

Your first major collection, Arabian Nights, launched in 2010 at Harrods. The Nomad Camel ring was a standout piece but also personal to you. Tell us more about that.

I always try to tell a story, if it’s mine or someone’s else. I was looking recently at some of the first pieces I made, and there was a three-knuckle ring with an elephant, and in it I could see the influence of Dalí and surrealism. I can see that in the camel ring, too. It makes me smile every day when I wear it. It’s got a bit of humor, a bit of surrealism, and a bit of pushing boundaries to it.

Ten years ago, you debuted the Superwoman ring, and it has become a kind of icon of your brand. What was the inspiration?

The Superwoman rings are so dear to me. They are inspired by the inherent inner strength that every woman possesses. How it started was I had a nearly three-carat kite diamond in my pocket, and I was going from one trade show up to the next one, kind of “speed dating” different stones to find a match for it. It took me two years to land on a match: a rubellite with a beautiful shape, not quite a triangle or a trillion.

I sold [the ring], and then I made another one, and I now do about seven to 10 editions of the ring per year. I try to dive into what these stones mean and what their energy is. And I create little mantras or titles for each ring, which are all engraved on the inside.

Although you have primarily worked in the high jewelry space, you started a demi-fine line called Atelier Romy in 2015—which you have recently paused. How did you come to that decision?

The goal of Atelier Romy was to create a ready-to-wear brand that made my jewelry accessible to everyone. But I was spending five hours out of my day on spreadsheets and shipping packages. If I wanted to be involved in making it grow into a bigger brand, it would require a different skill set than mine. I think Atelier Romy is ready to walk on without me and for somebody else to run it and keep it alive. I felt that it was time for me to go back to my roots. I wanted to return to the tradition of a client going to their corner jeweler to create something together. So it was really like going back to where I started: I capture your story with a stone, or your family heirloom gets re-created. For me it was best to just concentrate on that and let the other one go.

You’ve told me that your Bergdorf’s residency felt like a unique opportunity, and a fitting way to mark your 30-year milestone. Can you expand on that a little?

All of the retailers I have worked with have been very important to my growth as a jeweler, but often the team wanted three versions of one of the rings, or two rings in that color and 10 in those colors. And I was like, “But there is only one.” So it was very special to celebrate the 30 years at Bergdorf’s—I think it is the most beautiful store there is in the world. And they allowed me to bring what I wanted and show the storytelling behind the pieces. Obviously we curated a selection of my work, but it was very nice to show things that allowed you to see my “handwriting” in the designs.

Another thing about Bergdorf’s is that they allowed me to have one of my Mandela sculptures on the floor as well. I think it was the first time someone was allowed to bring a sculpture into the jewelry salon.

Looking ahead, what’s next for your brand?

I’d like to concentrate on the Superwoman ring on the commercial front, allowing clients to pick their stones and then build a ring from there. Maybe I will sell them online—I don’t know if [through] a store or something like that; I would need to find a supercute niche. Then maybe I can do more than just seven a year!

Alongside that, I would really like to give back to the next generation of “superwomen.” I’d like to start something where I can give back to girls in the industry through help with scholarships or funding, because I remember how hard it was for me.

And on the art and sculpture front, I want to learn how to carve marble and scale the sculptures up a bit and show them in a gallery or in a public space outside somewhere. But even I’m curious what’s next for me! And whatever that it is, it normally happens when I’m working on the bench. It’s ever evolving.

Top: Sabine Roemer, photographed earlier this year, dreaming up designs and working at her bench

Follow me on Instagram: @aelliott718

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine