The United Arab Emirates (UAE), chair of the Kimberley Process (KP) this year, had billed 2025 as the KP’s “Year of Best Practice.” Instead, the conflict diamond prevention scheme capped its recent meeting by again demonstrating its worst tendencies, as political polarization and a clotted decision-making process left most of its main goals unrealized.

The Kimberley Process’ annual plenary, held Nov. 17–21 in Dubai, not only failed to expand the KP’s definition of conflict diamonds—which the industry worked hard to make happen—but didn’t select a chair for 2026.

“Everybody from all sides left frustrated,” says Hans Merket, a researcher with the International Peace Information Service and a member of the Kimberley Process Civil Society Coalition (KPCSC). “That’s never a good sign.”

Prior to the meeting, the World Diamond Council (WDC)—which represents the industry at the KP—announced that African governments had agreed to enlarge the scheme’s definition of conflict diamonds to include human rights abuses.

The KP’s current definition is limited to “rough diamonds used by rebel movements to finance wars against legitimate governments.” The new definition would have included “violence carried out by…militias, mercenaries, organized criminal networks, private military and security companies, and other non-state actors; explicitly recognized diamond-mining communities within the KP’s mandate of protection; and added armed conflict and systematic or widespread violence to the list of actions covered by the Kimberley Process,” according to the WDC.

A few years back, reform-minded governments like those in the EU would likely have supported that change. But at last week’s plenary, the EU, Canada, the United Kingdom, Australia, Switzerland, and Ukraine all voted thumbs-down on the expanded definition, arguing it should include violence by “state actors.” That effectively killed the proposal, which required absolute consensus to pass.

The language about “state actors” has long been part of the KP definition debate. Proponents say it is needed because government armies and police forces have sometimes acted violently in diamond areas. However, many involved in the KP believed the EU specifically insisted on that language this time to target Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. (The EU’s KP focal point didn’t respond to a request for comment.)

Countries opposed to the “state actors” language—particularly attendees from Africa—claimed the verbiage could violate their sovereignty.

A statement from the 22-member African Diamond Producers Association (ADPA) issued post-plenary said that the definition change “was carefully drafted to avert an untenable situation of including language that would impact the sovereignty of participants.”

WDC president Feriel Zerouki tells JCK, “The term ‘state actors’ is never used in treaty agreements. We need to use U.N. language: non-state armed groups.”

On the other hand, Jaff Napoleon Bamenjo, head of the Cameroon-based NGO Relufa and current head of the KPCSC, says that not including government abuses would represent a “lowering of standards.”

“As civil society, we don’t want to be selective as far as actors whose violence is bad and actors whose violence is permitted,” Bamenjo tells JCK. “All actors who are perpetrating violence should be held accountable.”

He adds that “Ukraine is also concerned about its sovereignty. They said, ‘How can one KP country attack another KP country using proceeds from diamonds?’ So in all cases, it’s about sovereignty.”

Merket had always believed that with the Russian issue looming, any attempt to change the definition was an uphill battle.

“The EU would never accept a new definition in a scheme that gives conflict-free certification to Russian diamonds,” he explains. “From the outset, everyone knew it was a lost cause. It was an impossible conflict to resolve.”

Zerouki, however, thought the definition change had a shot.

“We were full of hope,” she says. “We got extremely close.”

Zerouki says the issue is unlikely to be taken up again until the next KP review and reform cycle, which starts in 2028.

“It’s not the KP that failed,” she says. “Some participants vetoed its evolution, but the direction has been set. The positive thing is the change in mindset: African countries know that diamonds are nation-building, and it’s time for the KP to reflect that. There’s a spirit to take it to the next stage.”

Even so, Ellah Muchemwa, the ADPA’s executive director, says that African nations went home “disappointed.”

“The impact of lower diamond revenue due to the current difficult market conditions is already being felt in many diamond producing countries,” Muchemwa tells JCK. “The KP is an important part of consumer confidence.

“We are now back to the narrow definition of conflict diamonds, which refers solely to rebel movements or their allies. The reality on the ground is that we don’t have as many rebel movements as we used to have 20 years ago, when the KP was formed.”

The five-day KP meeting ended without an agreement on what country should lead the scheme in 2026, though Ghana was approved as vice chair, which means it will take over as head in 2027.

Earlier this year, Israel nixed a bid by Qatar to head the KP in 2026. Prior to the plenary, Zimbabwe volunteered to serve as next year’s chair, then withdrew its offer at the last minute. A rumored bid from India never materialized.

During the meeting, the UAE—which has chaired the KP for the last two years—said it was willing to head the organization for another year. But South Africa’s delegation objected, saying the certification scheme was built on rotating chairs. The South African representative suggested instead that the KP secretariat head the scheme next year, but some thought that might violate KP rules.

“It’s not clear what will happen with no chair,” Merket says, noting that the plenary gave itself another two weeks to agree on a suitable candidate.

The selection of the chair “remains unfinished business” that will “require sustained engagement in the coming period,” said KP chair Ahmed bin Sulayem in his closing remarks.

Finding a KP chair has become difficult for two reasons. The first is politics—the world is a lot more polarized than it was a few years ago. In the last decade, Russia and the EU both headed the scheme without complaint; now the two are at loggerheads, and bids from both would be instantly vetoed. (Ironically, some once-controversial chairs, like Angola and Zimbabwe, would possibly sail through.)

The second reason is money. Serving as KP chair is expensive: The country must host two worldwide meetings, which requires conference and hotel space. Some KP members either don’t have the funds for that or don’t want to spend it. (Because of these expenses, the KP changed its rules so that two countries can head the scheme and split the cost. So far, none have stepped up.)

The money issue has even bedeviled wealthy countries—when the United States was chair, it didn’t properly budget for KP meetings, and had to ask sponsors to underwrite its events.

This year, the U.S. surprised attendees by not attending the plenary at all, not even virtually. It wasn’t clear if that was because of the government shutdown, which ended just prior to the meeting, or if the current State Department is no longer interested in participating.

“It feels like the U.S. is relinquishing its leadership in the world,” says Bamenjo.

He sees the current KP impasse as a reflection of our divided geopolitics.

“We don’t have multilateralism anymore,” Bamenjo says. “Politics is now bipolar. The two sides don’t talk to each other. There is no effort to find common ground.”

Indeed, the plenary’s conclusion was so rancorous that participants couldn’t agree on a final communiqué (again). The various factions issued a flurry of session-ending press releases, most of which blamed the impasse on the “Western bloc.” (The entire G7 voted against the new language except for Japan, which didn’t express an opinion, and the absent U.S.)

In his closing remarks, bin Sulayem said that “agreeing on an updated definition for conflict diamonds would have been a landmark for the mechanism.”

He noted that 30 countries—including every African attendee—endorsed the change, but a “very small minority” blocked it.

“Why deny Africa the victory?” he asked. “Why should the continent that carried the cost [of conflict diamonds] be told once again to wait politely while others resolve their ideological differences?”

The World Diamond Council, which generally stays neutral in these fights, complained that a “few participants chose politics over people.”

On the other hand, the European Union said its “position is clear: Proceeds from rough diamonds must never be used directly or indirectly to fund conflicts of any kind. Diamonds associated to armed conflict or systematic or widespread violence by state actors must also be labeled conflict diamonds.”

The KPCSC statement argued that one faction shouldn’t be blamed for blocking progress, since every proposal drew opposition. The group called for a “serious rethink of how the KP is implemented and how decisions are taken.”

In spite of all the session-ending bad vibes, bin Sulayem noted in his closing remarks that the KP had made considerable progress this year, by instituting digital security for its certificates and securing the long-term future of the KP secretariat.

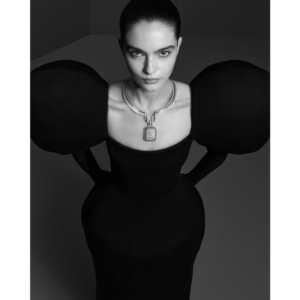

Top: World Diamond Council president Feriel Zerouki making her case (photo courtesy of the WDC)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine