GIA is known for many things: diamond grading, diamond education, and diamond devices. But what many don’t know is that it also grows diamonds.

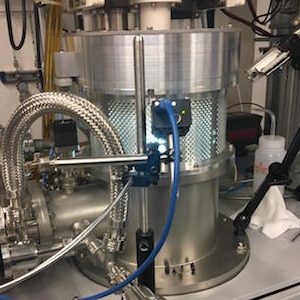

For the last five years, in the basement of a nondescript office complex in New Jersey, GIA scientists have grown diamonds using the chemical vapor deposition (CVD) method. Unlike the typical diamond producer, GIA doesn’t have a large row of reactors: It grows them one at a time, in different sizes and qualities.

It also doesn’t have any specified production target. When I ask executive vice president and chief laboratory and research officer Tom Moses how much it typically produces, he shrugs and says he is not sure.

“The most we’ve done is maybe a couple of hundred carats a year,” he says.

That’s because, unlike most producers, GIA doesn’t want to sell the diamonds. It wants to study them.

“We are trying to have as deep an understanding as we can have of the growing process,” says Moses. “So we are finding out what happens, almost in real time.”

It’s all, he says, in line with GIA’s 85-year-old mission: “To make sure the public knows what it’s getting.”

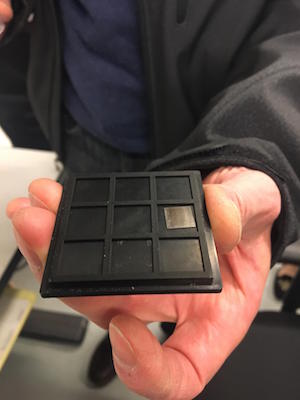

The New Jersey team mainly works on developing detection devices, including those that it markets, and proprietary ones for internal use. In its five years, the facility has become a substantial operation, which will keep growing (in every sense of the term).

“We started more as a garage shop,” says Moses. “I don’t think we are that anymore. There are a lot of very capable people with good technical backgrounds who are helping with this.”

Among those people is Dr. Jim Butler, who is one of the few people who can say he’s been growing diamonds for three decades. He started at the Naval Research Laboratory, then worked with Apollo Diamond, then became chief scientific officer at Diamond Foundry. Now, he is a consultant for GIA.

“GIA has done everything first-class,” he says, noting that the GIA set-up has the strongest safety measures of any lab he has ever worked in, as well as specialized diagnostic devices for its reactor.

“Very few factories will put any diagnostics on their reactor,” he says. The device gives him a real-time “view of the chemistry of going on.”

GIA specifically wanted its reactor to be flexible, he says. It constantly fiddles with the “recipe” and experiments with different impurities—all with the hope of learning every possible variation of diamond growing.

“We sometimes even grow crazy, weird samples,” says vice president of research and development Wuyi Wang, “just to see if we can identify them.”

GIA senior research scientist Ulrika D’Haenens-Johansson says that it wants to “tailor the types of atomic impurities that can be found in synthetic diamonds so that we can intentionally create samples that can be challenging to identify, just to make sure that we have the right procedures in place.”

The GIA lab has seen more attempts to pass lab-growns as naturals—and it expects that to continue, Moses admits.

“Over the last few years, there have probably been people systematically [mixing lab-grown and natural] to get some edge,” he adds. “It wouldn’t be the first time. You can buy synthetic rubies at the mine in Cambodia.”

One worrying trend GIA has noticed is high pressure high temperature (HPHT) producers using irradiation to remove phosphorescence. This could conceivably dupe certain image-based devices, which use that quality to detect whether a stone was grown by HPHT.

What’s particularly troubling about this is removing phosphorescence doesn’t improve the diamond cosmetically in any way. “You would only do it for deception,” Moses says.

GIA has not found any other treatments that are unique to lab-grown diamonds or any issues with color changes. A few “as grown” diamonds sometimes change color when exposed to heat or an ultraviolet lamp—but that is also true for certain natural diamonds (“chameleons”) as well. The color change is always temporary.

“There is so much confusion and misunderstanding that is going on right now,” says Moses. “[If people see a change in color,] they think it must have been a treated diamond. But it has nothing to do with a treatment.”

In addition to growing diamonds and examining what comes into its labs, GIA also purchases man-made stones throughout the world—sometimes through third parties.

Moses has noted a big leap in HPHT production from China.

“The largest factories in China produce 2,000 tons of this material a year. Granted, a lot of that is grit used for saw blades. But the presses that are used to do that are the same ones that are used to produce gem quality. If you are an industrial manufacturer, and you have these presses, and you sell [product] for 20 cents a carat, and you can make another 20 or 50 percent at your factory, why wouldn’t you? Especially since a lot of them are sitting there idle now.”

The material produced by HPHT often looks better than that grown by CVD, according to Wang.

“HPHT white is better than CVD white,” he says. “With CVD-synthetic, there is always going to be an internal strain. HPHTs look more transparent.”

Like many, he sees the diamond-production price going down. In fact, he believes that process has already started.

Moses says all this GIA activity—which comes at a not-insubstantial cost—informs not only its detection procedures, but recent decisions like the change to its lab-grown grading reports. It also wants to help advance the science of CVD production for industrial purposes.

Diamond growing is a rapidly changing field, and some have wanted GIA to act quicker. But Moses is more inclined to move slowly and thoughtfully.

“[Former GIA president Richard] Liddicoat used to say, ‘I think we should let it stew.’ It applies here. Let’s think this through. Let’s see what happens. See if we need to investigate it further. That concept is a wise approach for things today.”

And so as the market evolves, GIA is in New Jersey, letting things stew—and grow.

(Photos by: Rob Bates)

- Subscribe to the JCK News Daily

- Subscribe to the JCK Special Report

- Follow JCK on Instagram: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on X: @jckmagazine

- Follow JCK on Facebook: @jckmagazine